What kind of magical place combines a sanitation training center, community garden AND a remote control airfield?

Floyd Bennett Field, of course.

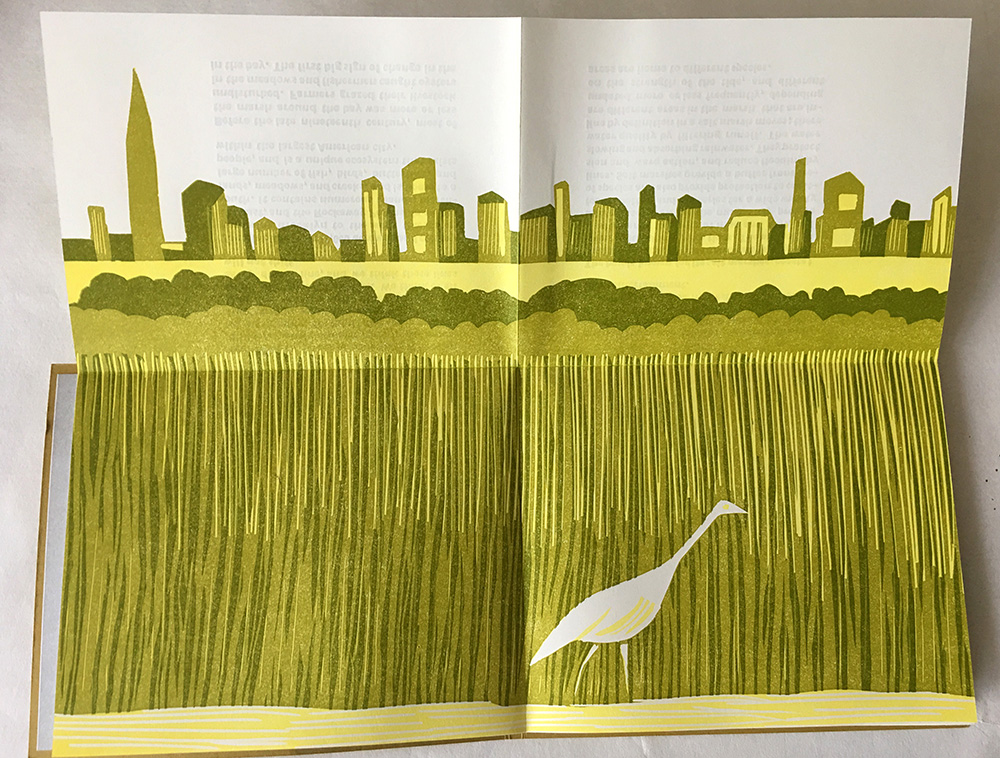

Floyd Bennett Field was New York City’s first municipal airport, opening in 1931. Airports are generally built on the outskirts of cities, in remote areas so that landing planes don’t hit anything. Floyd Bennett was built on land that had been known as Barren Island, one of the many bits and pieces of land in the marshes of Jamaica Bay, in the extreme southeast corner of Brooklyn. There was already a bare dirt runway used by a commercial pilot on the island, and when city planners decided that NYC needed its own airport, they chose this spot. The marshland around Barren Island was filled in with sand dredged from the bottom of Jamaica Bay, and many small bits of land were joined together and fused with the mainland. Flatbush Avenue was extended and straightened to provide pilots and passengers direct access to the rest of the city. A state of the art, amenities-filled airport was born, complete with new features like illuminated concrete runways and comfortable terminal facilities.

Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia wanted the new airport to be THE commercial airport for NYC. Newark International, the first area airport, had opened in 1928; he wanted the city to have its own airport. But commercial aviation was new, and the number of people who paid to take commercial flights was limited. Most airports paid the bills by freight, not by passengers. Newark had an exclusive contract with the Postal Service to provide freight transport, which in turn attracted other commercial airlines to work out of Newark. Flights that didn’t sell all their seats could make up their costs through cargo shipments for the post office. LaGuardia was only able to convince American Airlines to move their operations to the new airfield, and passengers complained that the commute all the way out to the end of Brooklyn took longer than even the trip out to Newark.

But commercial aviation was only part of the story of air travel at this point. Aviators were excited about the new facility and its modern conveniences, and the airfield hosted many record-breaking flights, time records, and air races between the two World Wars. Howard Hughes and Wiley Post both used Floyd Bennett for record breaking around-the-world flights. Female pilots like Amelia Earhart, Jackie Cochran, and Laura Ingalls made historic flights out of Floyd Bennett.

Since the commercial side of the airfield didn’t, uh, take off, the airfield became a base for the aviation units of both the Coast Guard and the NYPD. During the Second World War, the Navy used Floyd Bennett as a Naval Air Station. After the war, and up until the 1970’s the field was used as a support base for Navy, Air Force, and Marine units, as well as for the aviation units of the Coast Guard. But when the military moved their operations elsewhere, the field was decommissioned and began to decay. Control of most of the site was transferred to the National Park Service for inclusion in Gateway National Recreation Area, the sprawling multi-location National Park that encompasses many parts of Jamaica Bay as well as sites in northern New Jersey and Staten Island.

So today when you go visit Floyd Bennett, it seems a bit forgotten. It still houses an aviation base for the NYPD; the training center for the Sanitation Department is also there. There’s a public campground, as well as a hanger devoted to the restoration of Historic Aircraft. Volunteers and park rangers give tours on the weekends. Four hangers were renovated and taken over by a commercial tenant, the Aviator Sports and Event Center, which seems awful to me but I’m sure appeals to other people.

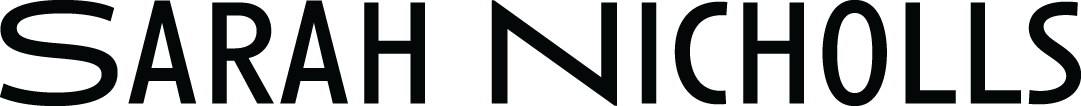

There’s a lot of empty space. Empty runways are a great place to fly kites, or drive remote control cars. An area of the site is a great place to hike, and offers good birding opportunities. Between the runways there’s also open grassland that people are kept out of as a wildlife habitat, and it provides cover and homes for grassland birds to live undisturbed. You can spend the afternoon completely alone wandering around what’s called the North Forty. Eventually you would end up at the Bay:

Where you can apparently kayak. Next to this bit is a Remote Control Airfield area, which apparently has a devoted community:

Spring migration is beginning; the Bay is right on the Atlantic Flyway, and I’m looking forward to going back over the next several weeks. More soon.