Volunteer Urban Plants

Cities and nature are a pair of ideas that push and pull against each other, in a relationship that lasts over time. The unplanned parts of nature that thrive in urban environments-think pigeons, squirrels, weeds- are often viewed as nuisances, eyesores, pests, or invasive. Or they become almost invisible to us; we have trained ourselves to just not notice the plants that push up through the cracks in the pavement.

Weeds are defined by their context. Weeds grow where you would prefer other plants to grow, or where no plants are intended to be at all. A weed is a plant out of place, that place being defined by the humans cultivating the land. How and why and where we define a plant’s proper place is part of a narrative we write that draws boundaries between nature and culture, between wildness and domestication, and weeds are the plants that blur these boundaries. People often expect landscapes to be moral, and the narratives we write about plants are how we decide what moral questions plants answer.

The plants we call weeds flourish in the company of humans. They’ve followed us around the earth, growing where we clear the forests, taking advantage of our transportation networks, enjoying the way we have disrupted settled ecosystems. Weeds benefit from disturbed land, empty lots, and neglected buildings, and they often grow back healthier after we cut them down. Weeds are patient, often waiting dormant for years until conditions are right. Weeds in urban areas are hardy enough to survive in harsh environments, and are often a main form of urban nature.

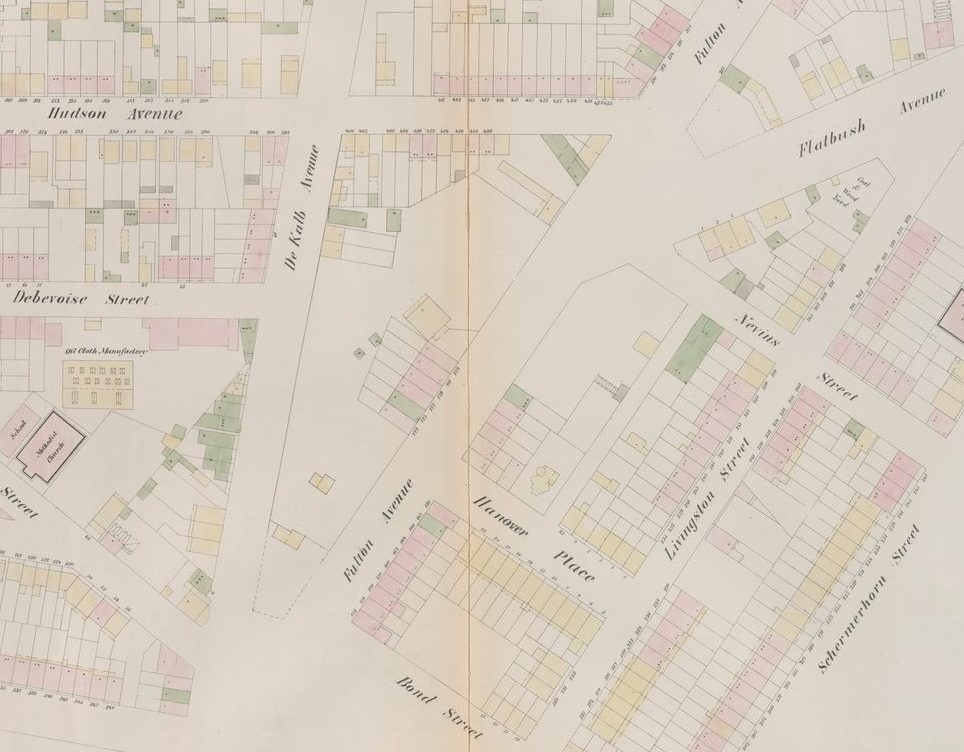

Some of the plants we call weeds in New York City are originally from elsewhere, carried here on purpose by people from elsewhere, or imported as a crop, or a commodity. Some of the plants we call weeds are native here; we sometimes use the word invasive to describe plants that have been here longer than we have. But some of the plants that live here came here accidentally, as a by-product of global trade, as stowaways. Ballast weeds is a term that describes these plants, especially ones that arrived as the waterfront in Brooklyn was industrializing in the nineteenth century. Ballast is one of the main ways humans have reconfigured the earth’s biome, shuffling the earth’s species at will. Ships ballast is extra weight carried below deck to provide stability. These days that is usually weight carried in the form of water; in the nineteenth century it would be whatever was at hand, including soil and rocks taken from one landscape, carried across an ocean to another. Erie Basin, the official terminus for the grain barges traveling through the Erie Canal, opened in 1864 on the southern edge of Red Hook, built by William Beard. Beard built this man-made extension of the harbor on landfill made up of ships ballast. Ships coming from Europe would dump their ballast in the harbor, then fill up with cargo and sail to their destination, literally transplanting one part of the earth to another, over and over again.

A few years ago there was an installation at Parsons School of Design, right across from a class that I was teaching, by the Brazilian artist Maria Thereza Alves. In the center of the room were small black bags filled with plants, all species classified as urban weeds. They were examples of plants that came to New York Harbor as seeds buried in amongst the ballast of shipping vessels, then dumped along the shoreline. Alves is interested in ballast flora as a living record of colonization, the transatlantic slave trade, and the economic foundations that the port of New York were built on. New Yorkers have been remaking the shoreline for hundreds of years, often by creating real estate where there was only water, through landfill, including ballast material. Ballast weeds are a remnant of that history.

Weeds in New York City offer a wide range of benefits, from helping to absorb excess rainfall, providing cooling in hot weather, to absorbing carbon, removing heavy metals from soil, and producing food and shelter for other species. Some of these benefits are especially important to communities vulnerable to climate change; green spaces can absorb water and slow down floodwaters. Volunteer trees like the Tree of Heaven provide shade in aging industrial places, and can help lower the temperature in the summer.

Invasiveness is a quality lots of urban plants have; people often think that only plants from other places are invasive, and use the words interchangeably. A plant that is invasive is one that spreads prolifically, and can dominate a plot of land. Native plants are understood to be the good kind of plants, and invasive ones, the ones from elsewhere, come in and take over and destroy a landscape. Xenophobia is trendy in gardening groups. In an urban landscape, it’s all about what can survive in the cracks, what can grow in soil that has had chemicals dumped on it, what can take advantage of what is left. Sometimes that means native plants, sometimes that means plants from other places. Sometimes these plants are the only ones that can survive, and by growing there, they are improving the soil to the point that eventually something else can join them.

There’s a block of Franklin Avenue near where I live that contains the remnants of what used to be a huge brewery complex. More recently part of it was used by a spice importer, and the entire block smelled like cumin, turmeric, and cinnamon. Most of the land is covered in weeds, a vast meadow of spontaneous volunteer plants taking up as much space as they can take from the buildings nearby. In the summertime I like to take that route home on my bike and as I coast downhill I can feel the temperature drop, the plants absorbing the heat radiating off concrete. That land was sold to a developer a while back; the spice factory closed and the block no longer smells of spices. But the weeds are still there for the moment and I plan on enjoying their benefits while I can.

If you’d like to see and learn more about weeds, take a look at the Virtual Bush Terminal Wildflower Walk made by my friend James Walsh.