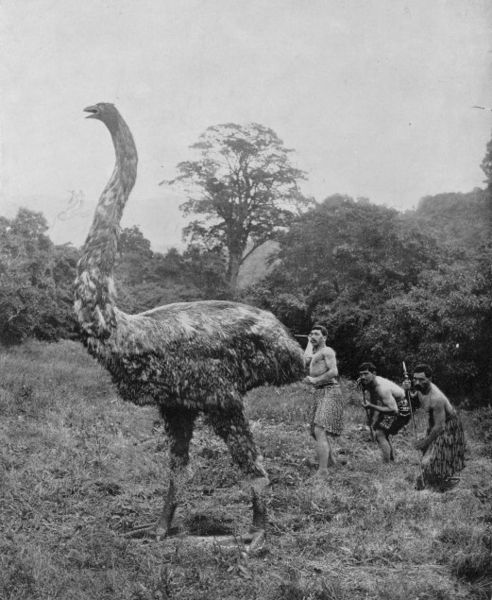

The Moa were a family of large ancient flightless birds endemic to New Zealand. The two largest of the nine kinds found there were about 12 feet tall and weighed in at 500 pounds. They had small heads, and were completely wingless, lacking even the stubby vestigial wings of other flightless birds; they were the dominant herbivores in the neighborhood. For millions of years they flourished, then abruptly disappeared, around the time the first Maori settlers reached New Zealand in the late 13th century.

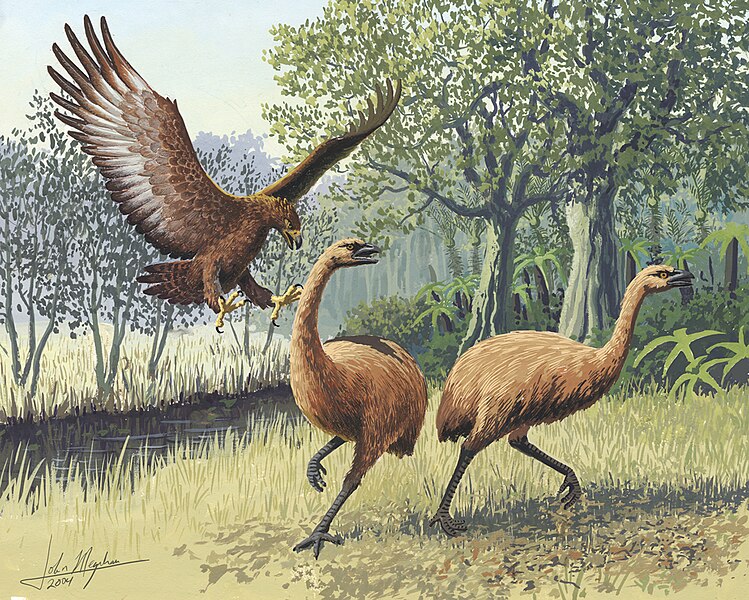

The Moa were the last of the Pleistocene megafauna-giant animals including mammoths, mastodons, aurochs, giant sloths and moas-to disappear from the earth. There’s been a lot of discussion of why the megafauna are gone, and how much humans had to do with it. A combination of factors-the arrival of homo sapiens, climate disruptions, volcanic eruptions, and disease- probably led to the extinction of many of these animals, but the moa’s disappearance were the exception, and can definitively be tied to overhunting by humans. Archaeologists know that the Maori ate Moa of all ages, as well as the birds’ eggs. We like to think of indigenous people as living in harmony with nature; the Moa complicate that story. The large birds offered sizable meals, and archaeologists have found piles and piles of the birds’ bones in excavated sites. When we arrived on the islands of New Zealand, humans were the first mammals other than bats the birds had even seen. Their only possible predator before us was the Haast’s Eagle (another impressively-sized bird). Researchers analyzed DNA from discovered bird skeletons and came to the conclusion that the Moa population was booming in New Zealand right up until the arrival of the Maori, at which point they disappeared very fast. Most, if not all, were gone by 1400.

Even today, though, some people hold out hope that moas survive somewhere. Gigantic prehistoric birds appeal to the imagination. Some hotels in New Zealand even offer to take tourists into the mountains to look for them, though killjoys will point out that these birds are too big to walk around undiscovered for long.

Cryptozoology is one of the glorious things I’ve discovered while researching extinct birds. There is a range of animals this term applies to; in general, cryptozoology is the search for animals whose existence has not been proven. This could mean animals that once definitely existed, but are now considered extinct-many extinct birds, like the moa, can fall into this category, as do creatures like dinosaurs, mastodons, and the like.

It can also mean animals that really do exist somewhere in the world, but most likely not in the places cryptozoologists are looking for them. Panthers in Britain is my favorite example of this category, called Phantom Cats, or Alien Big Cats.

Other animals (sometimes called cryptids) pursued by cryptozoologists include creatures that lack physical evidence but appear in myths, legends, or anecdotal evidence, like Bigfoot, Chupacabra, the Yeti, and the Loch Ness Monster.

Confusing the line between real and not-so-real are the animals claimed by cryptozoologists as former cryptids, which are now real, verified-by-science-animal species, like the okapi, the komodo dragon, and the mountain gorilla. The Okapi, ( a fairly unlikely looking animal, you have to admit) is the mascot of the now-defunct International Society of Cryptozoology.

The International Society of Cryptozoology (ISC) was a former professional organization founded in 1982 in Washington, D.C. It ceased to exist in 1998 due to financial difficulties. It was founded to serve as a scholarly center for documenting and evaluating evidence of unverified animals. According to the journal Cryptozoology, the ISC served “as a focal point for the investigation, analysis, publication, and discussion of all matters related to animals of unexpected form or size, or unexpected occurrence in time or space.” Despite the existence of such a center, cryptozoology is generally regarded as a pseudoscience.

If all of this has whetted your appetite for unverified animals, let me point you in the direction of this excellent book: The Ghost with Trembling Wings: Science, Wishful Thinking and the Search for Lost Species, by Scott Weidensaul. He covers the gamut of real and not-so-real animals, ranging from the once existing to the imaginary, and why the imaginary and the elusive are so damn seductive.