Collectors in the nineteenth century weren’t just interested in raiding nests for eggs, or collecting birds to be kept on mantelpieces. There was also the exploding market for hats with birds on them:

Hats adorned with real feathers, wings, and stuffed whole wild birds were the height of fashion in the late-19th century. Woodpeckers, blue jays, waxwings and quails: all were popular adornments, but most prized were ostrich, peacocks, pheasants, egrets, vultures, eagles, swans, herons, and turkeys, all coveted for their dramatic plumage.

The trade was fairly merciless. Hunters would kill and skin adult egrets during breeding season (when their wispy feathers were particularly attractive) and leave the orphaned nestlings to starve to death. The millinery trade took a tremendous toll on bird populations – 200 million wild birds per year by some estimates. Numbers of the most hunted species declined quickly.

New York and London were two main centers of the trade in feathers. Colonial expansion across the globe and the exploration of foreign lands had brought new and exotic specimens to the European marketplace throughout the century. New York was one of the places that helped bring these new specimens to Europe, including previously unknown varieties of birds, fuelling the fashionable demand for feathers, wings and even entire birds as decoration.

New York and London were two main centers of the trade in feathers. Colonial expansion across the globe and the exploration of foreign lands had brought new and exotic specimens to the European marketplace throughout the century. New York was one of the places that helped bring these new specimens to Europe, including previously unknown varieties of birds, fuelling the fashionable demand for feathers, wings and even entire birds as decoration.

In the US, two women banded together to fight the slaughter. Two Boston Socialites, Harriet Hemenway and her cousin Minna Hall, started a boycott of the trade, which gained steam due to their social connections. They sent out circulars protesting the practice and hosted tea parties where they educated their guests about the cost to bird life. Their tea parties grew in popularity and culminated in the founding of the Massachusetts Audubon Society, and later, passage of the Weeks-McLean Law, also known as the Migratory Bird Act, by Congress on March 4, 1913. The law banned market hunting and the interstate transport of birds.

There’s a fascinating online exhibition here called Fashioning Feathers, if you’re interested. There’s also a great article here by the always entertaining Lapham’s Quarterly.

New York and London were two main centers of the trade in feathers. Colonial expansion across the globe and the exploration of foreign lands had brought new and exotic specimens to the European marketplace throughout the century. New York was one of the places that helped bring these new specimens to Europe, including previously unknown varieties of birds, fuelling the fashionable demand for feathers, wings and even entire birds as decoration.

New York and London were two main centers of the trade in feathers. Colonial expansion across the globe and the exploration of foreign lands had brought new and exotic specimens to the European marketplace throughout the century. New York was one of the places that helped bring these new specimens to Europe, including previously unknown varieties of birds, fuelling the fashionable demand for feathers, wings and even entire birds as decoration.

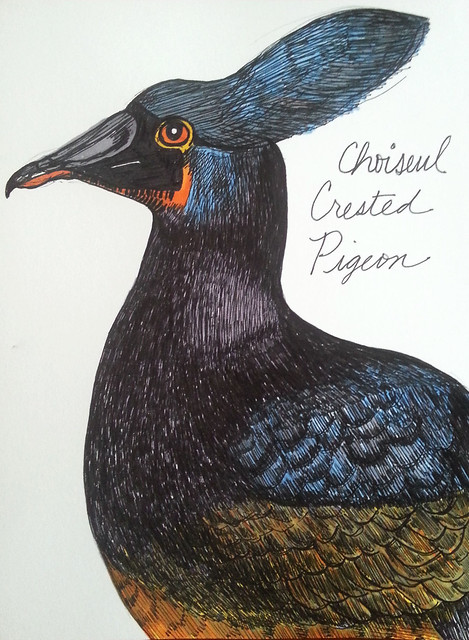

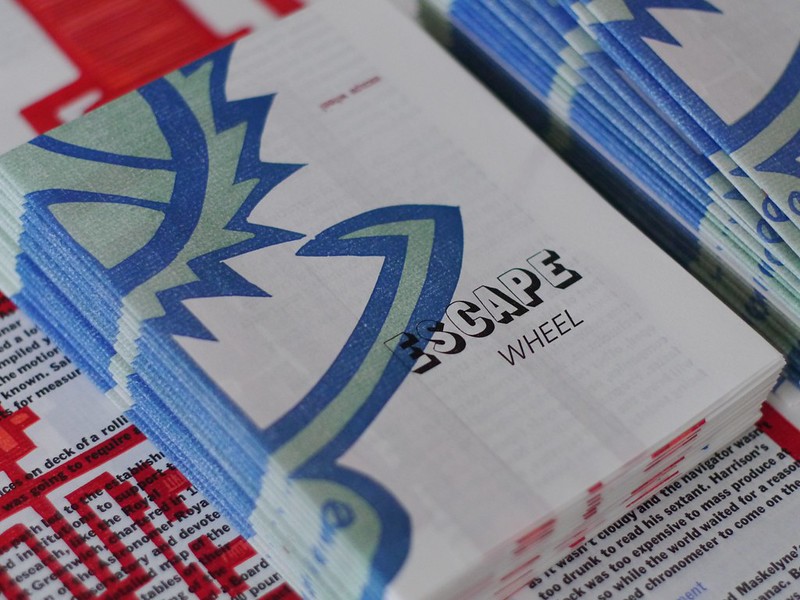

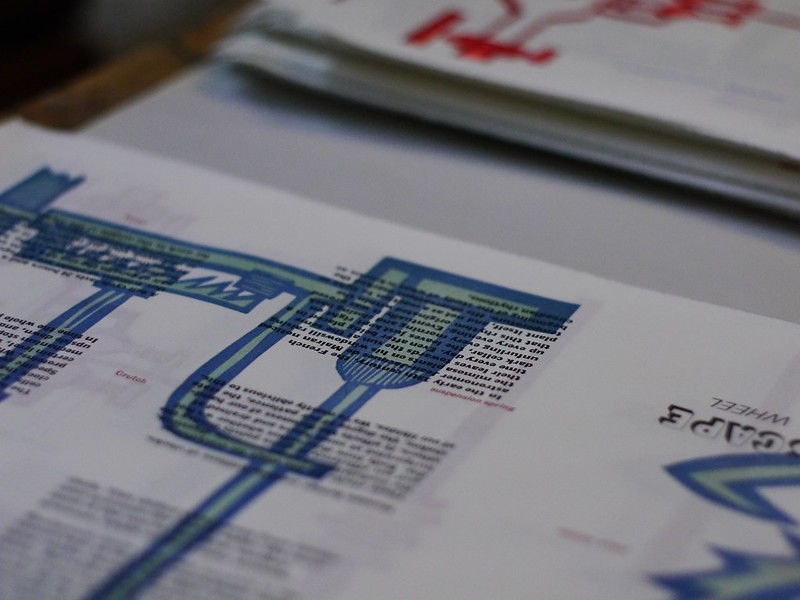

So, as I’ve mentioned, I am slowly working on a field guide to extinct birds, partly because paper field guides are one of the kinds of printed books that are probably going to disappear (like dictionaries, encyclopedias, atlases, travel guides, etc.) to be replaced by easily portable, easily updated apps. One of things that apps are better at is recording and communicating birdsong. I love the ways that writers have translated birdsong into printed language. (

So, as I’ve mentioned, I am slowly working on a field guide to extinct birds, partly because paper field guides are one of the kinds of printed books that are probably going to disappear (like dictionaries, encyclopedias, atlases, travel guides, etc.) to be replaced by easily portable, easily updated apps. One of things that apps are better at is recording and communicating birdsong. I love the ways that writers have translated birdsong into printed language. (

After Audubon, ornithology began to take shape as a field of study. As an example, one of his protegees, Spencer Fullerton Baird, helped to create and direct the National Museum of Natural History for the Smithsonian. Baird cultivated a far-flung network of collectors and ornithologists who sent him specimens of birds. Many of them were US Army officers patrolling the frontier, since they had access to the most remote areas of the country.

After Audubon, ornithology began to take shape as a field of study. As an example, one of his protegees, Spencer Fullerton Baird, helped to create and direct the National Museum of Natural History for the Smithsonian. Baird cultivated a far-flung network of collectors and ornithologists who sent him specimens of birds. Many of them were US Army officers patrolling the frontier, since they had access to the most remote areas of the country.

Eggs were the focus of the most extreme kind of collecting obsession. Oology, the study and collection of eggs carefully blown clean of their contents, was a genuine rage in North American and Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Oologists were tremendously competitive and each aimed to assemble the most complete collections. Eggs were usually taken not one at a time, but in entire clutches from the nest.

Eggs were the focus of the most extreme kind of collecting obsession. Oology, the study and collection of eggs carefully blown clean of their contents, was a genuine rage in North American and Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Oologists were tremendously competitive and each aimed to assemble the most complete collections. Eggs were usually taken not one at a time, but in entire clutches from the nest.