New projects

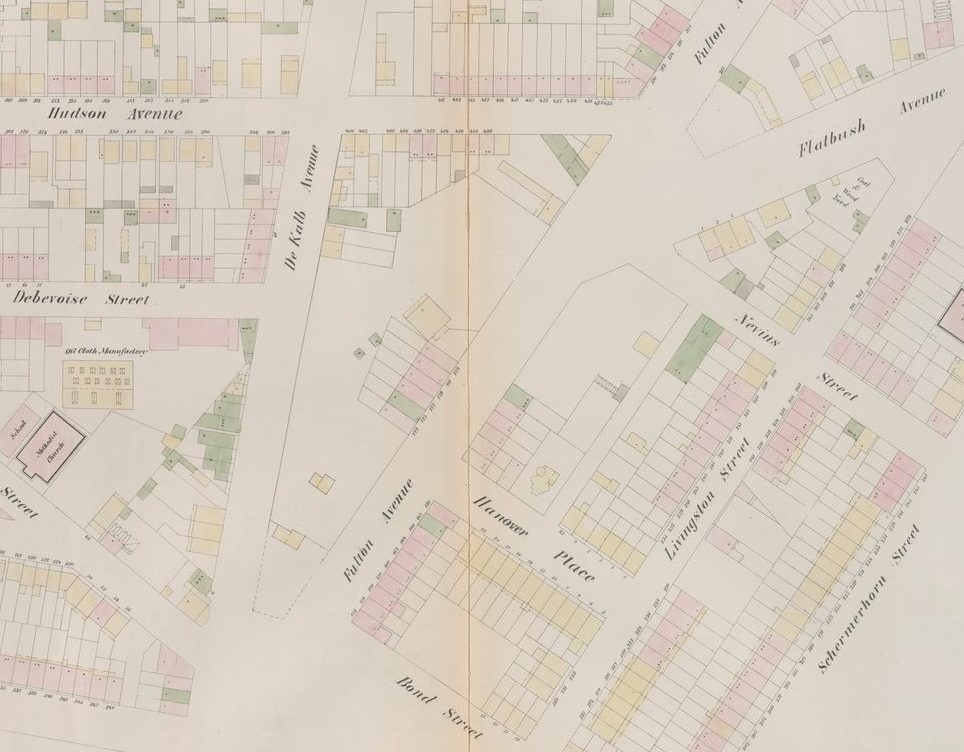

I’ve been working on not one but TWO books this year. One will be about Governor’s Island and is based on my work and research last fall. But what I want to talk about today is the other book, a collaboration with Amanda Deutch.

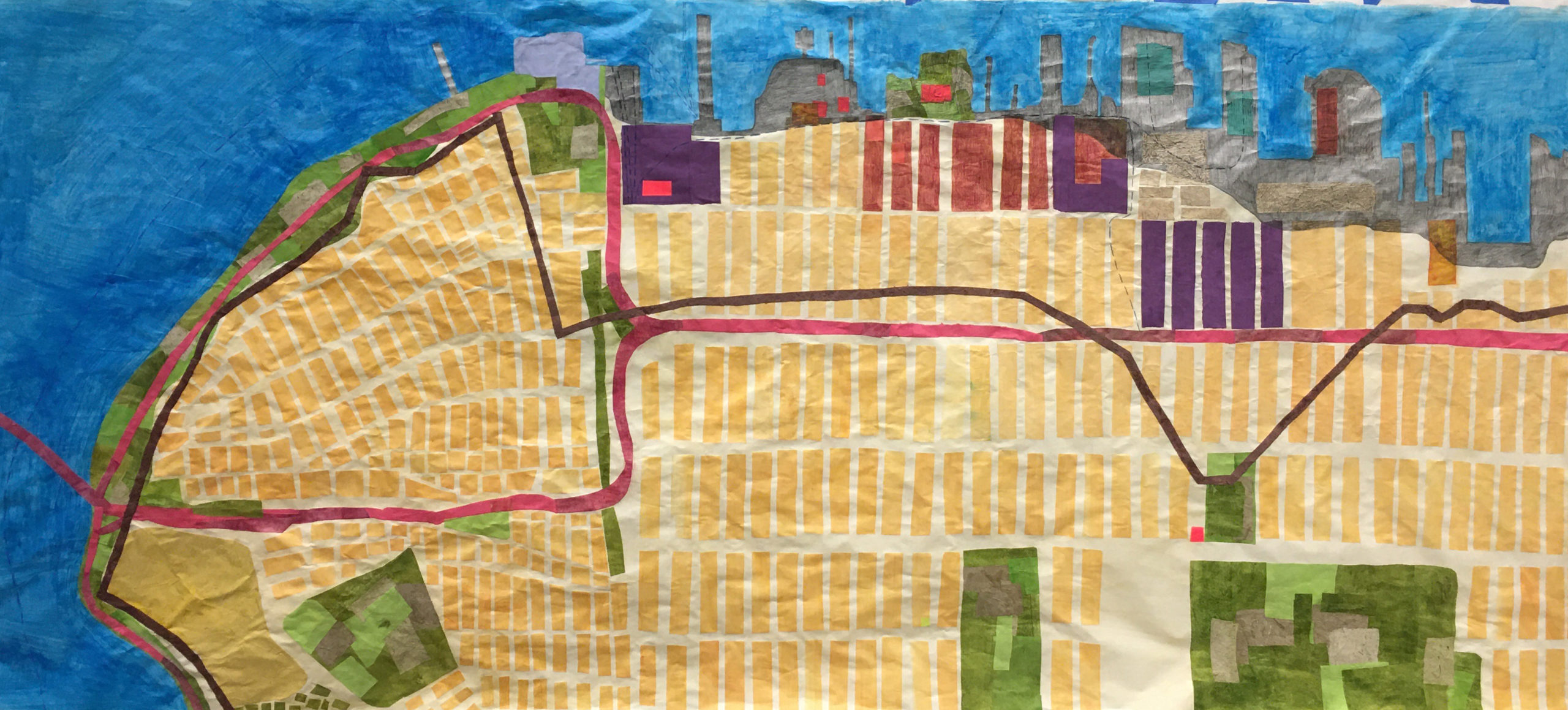

These are some images of pages in progress that I printed in August at the Center for Book Arts. Amanda came to me with a manuscript of poems that she’d written earlier this year called wild anemone.

All the poems are named for a different wildflower, then goes off in different directions. Some talk about the cityscape, some are more internal, some warp into automatic writing, sometimes the language breaks down entirely. She calls them “witchy little poems” and asked if I might be interested in making something out of them.

I’ve spend some time over the last few years making paper and inks from weeds and wildflowers in NYC, and writing about weeds and wildflowers, and I thought it was a good fit for me, and also I just loved the poems, they were so strange. So I said yes. I had some pressure prints around the house and this May I made a simple rough mock up:

So the idea was to mix printed elements with the poems and with layers of handmade and pigmented paper that are made from locally foraged plants, that conceal and reveal the texts. I was excited to get started.

Coincidentally, I had previously registered for a fantastic paper making class this summer at Womens Studio Workshop, a class on using natural and found color in paper taught by Hannah O’Hare Bennett. For a week in July I was surrounded by brilliant natural color- it was an amazing time.

So after spending all of this time around color, I not only gained a lot more knowledge on how to use natural pigments, but my palette shifted. When I came back I printed the final versions of the pressure prints, and the text for the book:

I think the yellows became more golden and the colors overall seem more vibrant than in the mockup. I’m now working on making more handmade paper for the edition. I will be using both foraged fiber and foraged color, including goldenrod, milkweed, and jewelweed:

I want to make sure to have a lot of golden yellows and rich purples, which is what I always think about when I think about wildflowers in the city, especially in the fall.

Some of the color may come from Governor’s Island, which I have more to say about soon. This photo is from last fall, when I was in residence there. (More soon about that.) I hope to have it completed for next February’s Codex Bookfair.